Treatment of Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction (HFpEF) in Dogs and Cats (Part 1)

01. Overview

Heart failure (HF) in dogs and cats is classified into three subtypes: heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF, LVEF ≤50%), heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF, LVEF ≥60%), and heart failure with mid-range ejection fraction (HFmrEF, LVEF 50%–59%).

Clinically, veterinarians often assess heart failure using EF values, with a common tendency to regard LVEF <50% as the diagnostic cutoff for HF. This article elaborates on the relationship between cardiac diseases and EF in diagnosis, as well as the corresponding treatment strategies.

The pathophysiology of HFpEF is primarily characterized by diastolic dysfunction (myocardial relaxation impairment or stiffness). As emphasized in clinical lectures, a normal EF value does not equate to normal cardiac function—it is merely an echocardiographic parameter. Clinical diagnosis must integrate clinical manifestations, along with considerations of impaired cardiovascular coupling, inflammatory status, cardiac chronotropic incompetence, and pulmonary hypertension. Notably, modern HF assessment has shifted from focusing on reduced systolic function to impaired diastolic function (i.e., HFpEF as diastolic heart failure).

Recommended ultrasound devices for EF measurement and diastolic function evaluation: PT60, BPU100.

Figure 1

Left ventricular long-axis view in hypertensive heart disease

Figure 2

Left ventricular long-axis view in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

02. Epidemiology

- In cats: HFpEF is predominantly associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

- In dogs: Common etiologies include diabetes mellitus, atrial fibrillation, obesity, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, and respiratory tract stenosis.

03. Diagnostic Criteria for HFpEF

- Normal left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF ≥60%), measured via standardized echocardiography (recommended device: BPU60C).

- Cardiac structural abnormalities (e.g., left ventricular hypertrophy, left atrial enlargement, and/or diastolic dysfunction) without valvular heart disease (assessed via PT50 ultrasound for precise structural quantification).

- May coexist with systolic dysfunction or occur independently.

- B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) has limited reference value (controversial in clinical practice).

- Abnormal echocardiographic parameters (E/A ratio, e’/a’ ratio) and/or presence of atrial fibrillation (detectable via BPU50 ultrasound combined with electrocardiography).

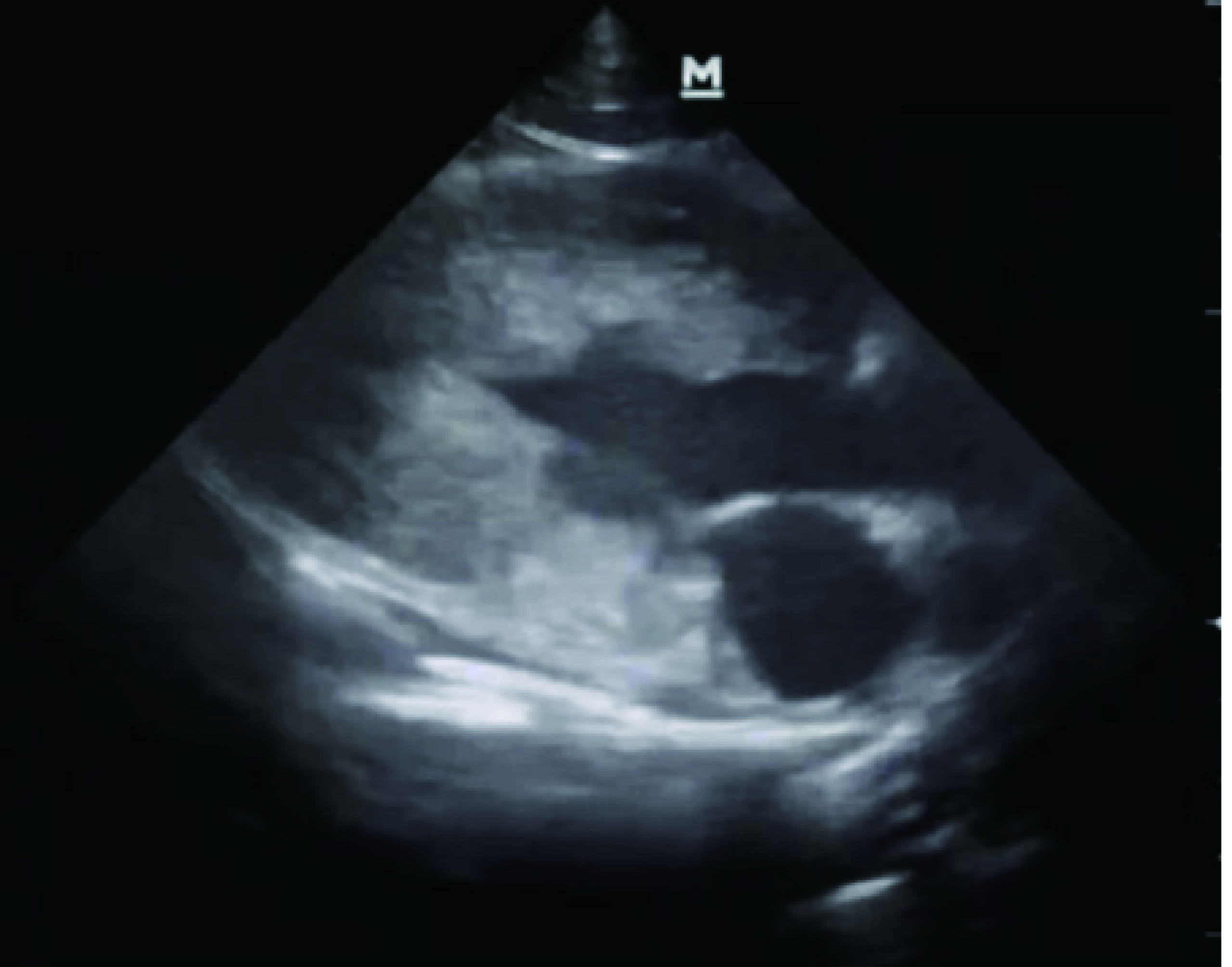

Figure 3

E/A ratio <1

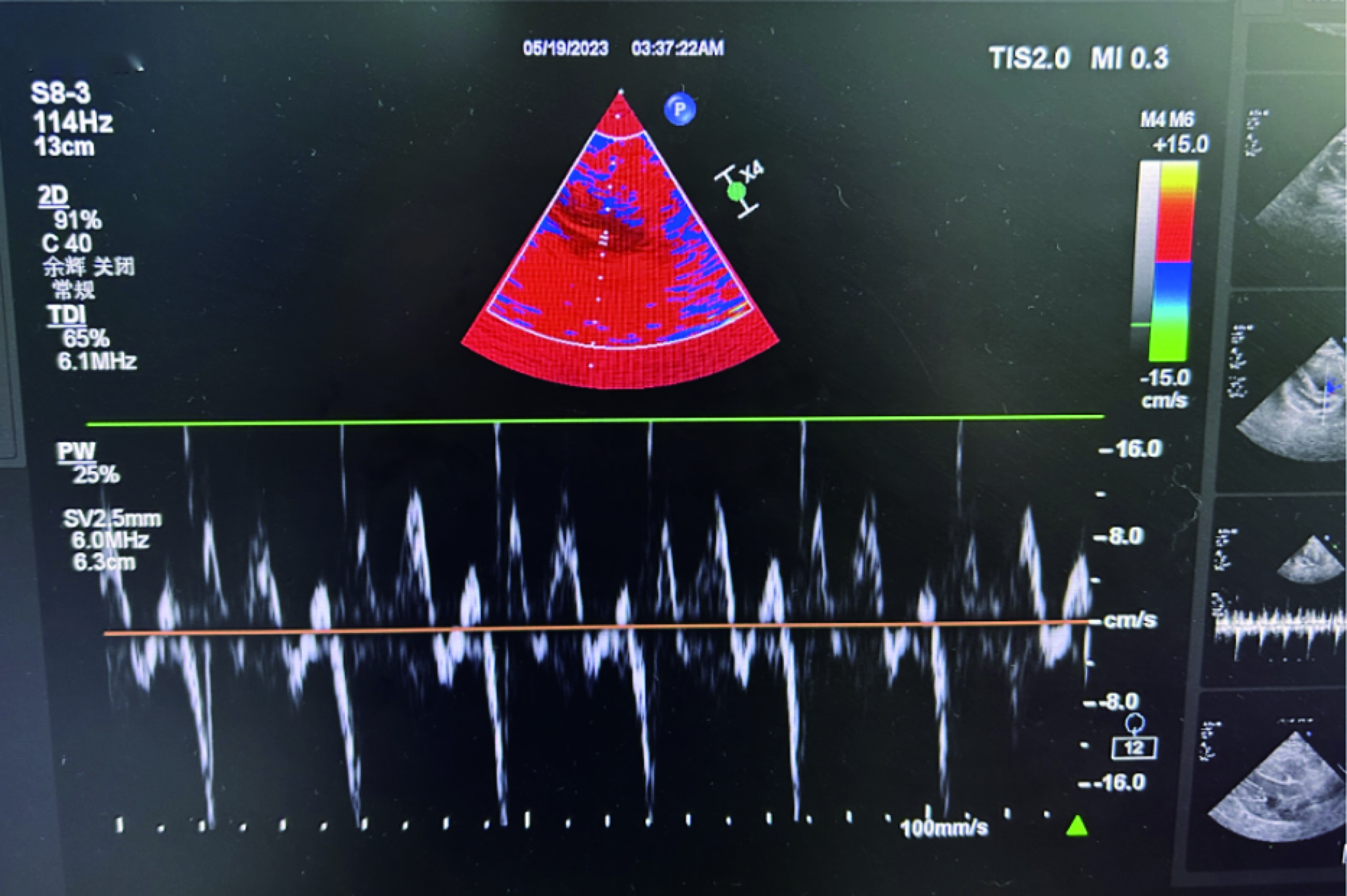

Figure 4

Tissue Doppler imaging (TDI) showing e'/a' ratio <1

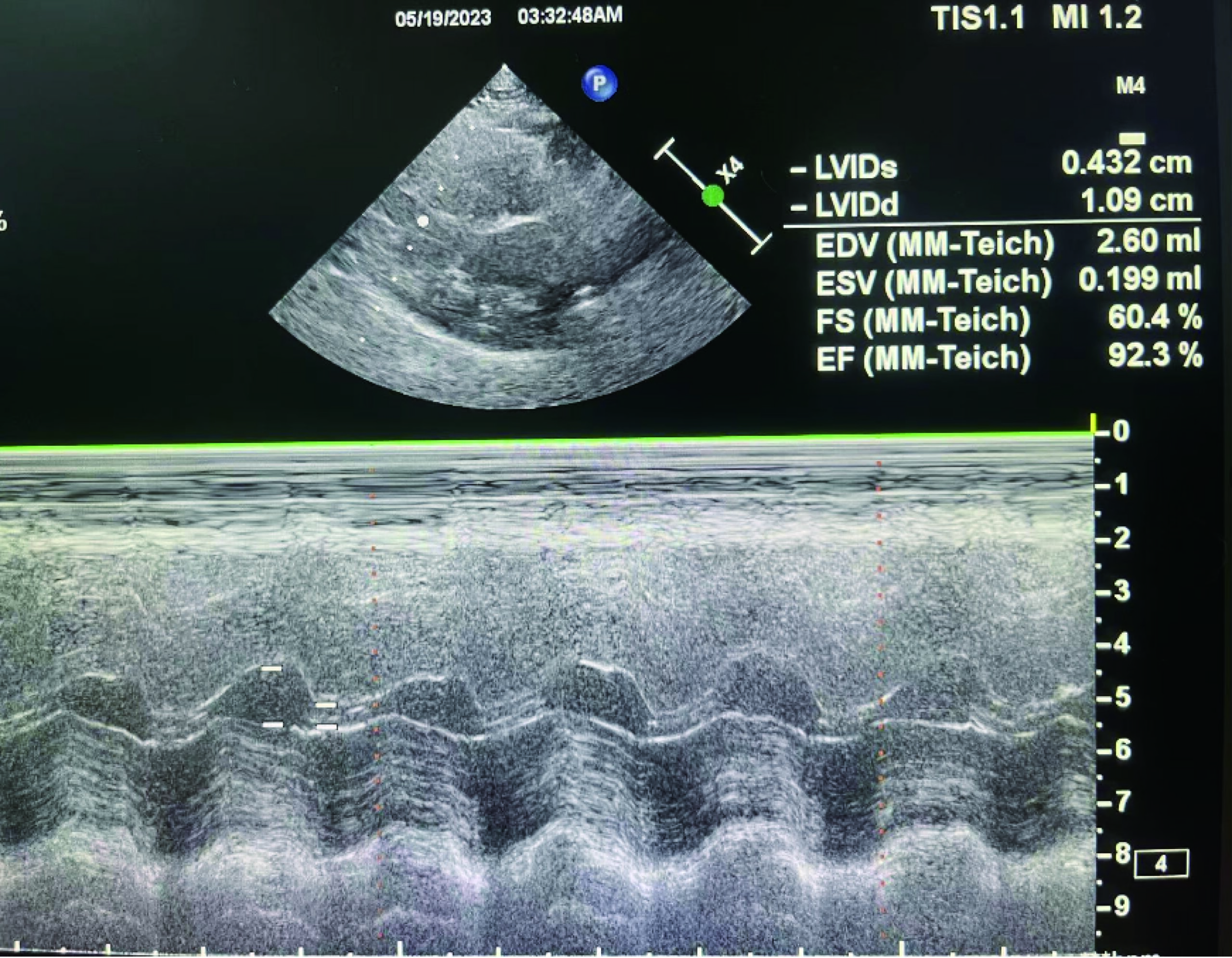

Figure 5

EF >92% (measured via MM-Teich method)

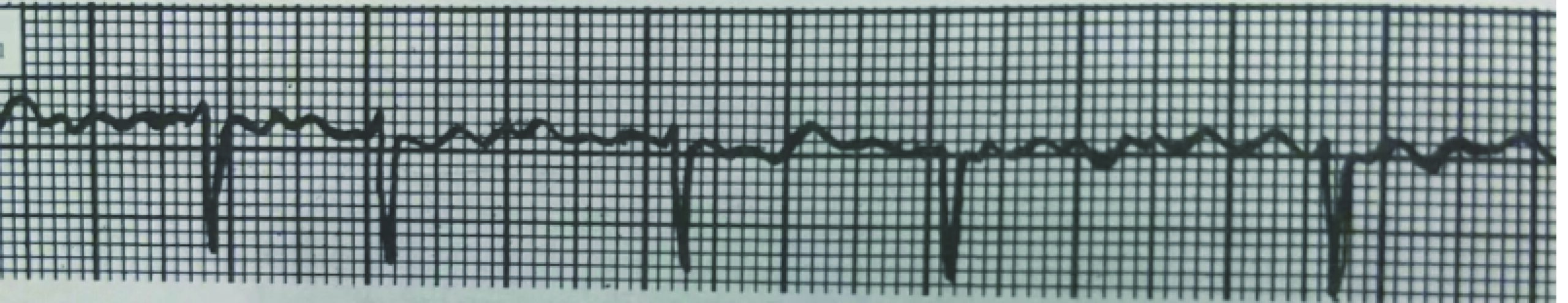

Figure 6

Atrial fibrillation

04. Treatment Principles for HFpEF

-

Clinically, HFpEF and HFmrEF are managed using similar strategies, so the treatment approaches described herein also apply to HFmrEF. Due to distinct pathophysiological mechanisms, HFpEF requires different management compared to HFrEF. The core treatment principles focus on the following aspects:

- Improve ventricular diastolic function.

- Correct fluid retention.

- Treat comorbidities (e.g., hypertension, atrial fibrillation, renal insufficiency).

05. Summary

What is the appropriate management when echocardiography (e.g., using BPU100 ultrasound) detects hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with an EF of 95%? The next article will detail specific HFpEF treatment protocols, including management of HFpEF associated with hypertension, diabetes mellitus, atrial fibrillation, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, renal insufficiency, and anemia.

This article is clinically applicable for veterinarians managing hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, hypertensive heart disease, and respiratory tract stenosis in dogs, aiming to enhance diagnostic accuracy and medication decision-making.